Dhamma Brothers

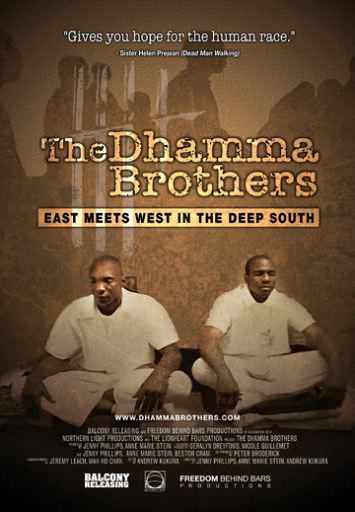

The Dhamma Brothers

“For the first time, I could observe my pain and grief. I felt a tear fall. Then something broke, and I couldn't stop sobbing. It felt as if I were cleansing myself. I found myself in a terrain where I had always wanted to be, but never had a map. I found myself in the inner landscape, and now I had some direction.”

- Omar Rahman - inmate at Donaldson Correctional Facility

“On the third day of meditation, I began to feel calm. And then and there, for the first time in my life, I was really ready to deal with me. A lot of guys was afraid to deal with Big Ed. And now I was ready to take him on, right there on that meditation mat.” - Edward Johnson - inmate at Donaldson Correctional Facility

The words of these men, prison inmates, capture the essence of The Dhamma Brothers. Their voices ring with the power and the truth of their experience. It is unlikely that the viewer, after seeing this film, will be able to return to old clichés and stereotypes about men behind prison bars. The Dhamma Brothers documents the extraordinary convergence of an overcrowded, understaffed maximum-security prison -- considered the end of the line in the Alabama correctional system -- and an ancient meditation program. East meets West in the Deep South.

Donaldson Correctional Facility is situated in the Alabama countryside southwest of Birmingham. 1,500 men, considered the state's most dangerous criminals, live behind high security towers and a double row of barbed and electrical wire fences. Yet within this dark environment, a spark was ignited. A growing network of men was gathering to meditate on a regular basis. Intrigued by this, Jenny Phillips, cultural anthropologist and psychotherapist, first visited Donaldson Correctional Facility in the fall of 1999. She planned to observe the meditation classes facilitated by inmates and to interview the inmate meditators about their lives as prisoners. As she met with the men, one by one in the privacy of an office, she was drawn in by their openness and willingness to talk freely about themselves. High levels of apprehension, distraction and danger characterize their lives as prisoners. Even though many of these men will never be released from prison, they were thirsty for meaningful social and emotional change. What she heard there was difficult to forget. It left her wondering if it were possible to live with a sense of inner peace and freedom within the harsh, violent prison environment.

As a meditator herself, Jenny knew that meditation directly addresses the issue of personal suffering, and offers a simple yet powerful means for obtaining relief from that suffering. But were these ancient ideas, as described in the teachings of the Buddha 2500 years ago, now relevant? Could the framework of this approach to suffering be translated into some basic principles of treatment that would be applicable to 21st century North American prisoners? Were these prisoners, many of them survivors of personal trauma, even capable of withstanding the emotionally and physically demanding experience of a 10-day meditation retreat? More important, was it possible for these men, some of whom had committed horrendous crimes, to change?

When returning home to Massachusetts, Jenny contacted the Vipassana Meditation Center in Shelburne Falls, Massachusetts, part of a worldwide network of centers dedicated to preserving meditation according to the teachings of Buddha. After a year of planning between the prison and the Vipassana staffs, in January 2002, Donaldson Correctional Facility became the first prison in North America to hold a 10-day Vipassana retreat.

The Dhamma Brothers tells a dramatic story of human potential and transformation as it closely follows and documents the stories of 36 prison inmates as they enter into this arduous and intensive program. It will challenge assumptions about the very nature of prisons as places of punishment rather than rehabilitation. Despite the extreme difficulty in obtaining permission to film inside a prison, the Alabama Department of Corrections allowed a film crew to document, not only the Vipassana retreat, but many other scenes and settings revealing the daily lives of prisoners and staff. The Dhamma Brothers draws the viewer in through memorable interviews with the inmates, the prison staff, the inmates' families, and members of the surrounding community.

The film combines verite footage and, because some of the inmates' crimes attracted significant media coverage, also includes archival television reports which appeared at the time of the crimes. In interviews immediately before the Vipassana retreat, the men openly express fear and trepidation, wondering what they will find when they look deeply within and face the consequences of past actions and trauma. They are shown packing their scant belongings and preparing for the journey inside, a very short walk down the prison corridor but a sea change in their lives as prisoners. We observe the transformation of the prison gym, a frequent site for violent battles among inmates, into a monastery, a separate, restricted place in which the inmate students can eat, sleep, and meditate in total seclusion from the rest of prison society. The Vipassana teachers, Bruce and Jonathan, prepare to live and meditate with the inmates. Teachers and inmates, men from culturally different worlds, are locked together in a dramatically revealing process. This is, most likely, the first time non-inmates have ever lived among inmates inside a prison.

We follow the men day to day on the retreat. Seated on meditation mats on a red rug donated by the Warden, wrapped in navy blue blankets, the men sit still in silence as they journey inside. Their days are punctuated by a strict daily routine of eating, sleeping and meditating.

Among those portrayed in the film are the following: OB: Sentenced to three life sentences for a drive-by shooting in which two were injured and one died. OB came to the U.S. from Africa as a teen-ager seeking freedom from civil war and violence in Uganda. When he was arrested in a high profile crime, he was

portrayed as a “ruthless animal from Africa”.

Grady: Serving life without parole, rescued from Death Row by a defense attorney the day before he was scheduled for execution. Grady discusses his crime as that of standing by while two men he had just met that day slaughtered a third man. He describes being frozen with fear while he witnessed the brutal attack, and then twenty years of guilt and remorse for being afraid to intervene.

Big Ed: Prison gang leader, held in a segregation cell for six years. Ed spent his years both in the streets and in prison ripping and running, with a reputation for being a tough guy.

In individual interviews after the Vipassana retreat, the men tell their tales of pain and self-discovery. During group interviews, the spiritual warriors of Donaldson Correctional Facility discuss their collective experiences and vow to try to maintain their nascent sense of solidarity. In the nameless, faceless anonymity of prison life, where daily life is organized around social control and punishment, Vipassana has offered an alternative social identity based on brotherhood and spiritual development. But, has the retreat been genuinely transformative for the men? Or, as the Warden suggests, could they just be faking these changes to look good to the parole board? Is the transformation sustaining?

In response to these questions we returned to the prison to interview the prisoners and prison staff to see the impact of the retreat upon their daily lives. We visited the homes of prisoners' families, and talked to them about their observations about the impact of the retreat. Also included are on-going personal letters and diaries from the inmates who have continued to corresponding with Jenny Phillips over the past four years.

The stories of the men at Donaldson Correctional Facility are those of the unseen, unheard, and underserved. This film shines a spotlight upon society's outcasts and untouchables. By witnessing these men on their odyssey into their misery to emerge with a sense of peace and purpose, there arises in the viewer identification with their quest. It is difficult to distance oneself from these men.

Suffering is universal. The men at Donaldson are learning to become free within even while their bodies are imprisoned. This film explores how free people are imprisoned inside, and will posit the possibility of freedom from that which imprisons us all. This is a compelling story showing the capacity for commitment, self-examination, renewal and hope within a dismal penal system and a wider culture bent on demonizing prisoners. We trust that the public airing of this documentary will engender a more informed understanding of the humanity within men and women serving time, and will encourage a call for the implementation of similar rehabilitation programs around the country.

This film will be of direct benefit to prisoners. Those most directly affected by the problems endemic in American prisons, the prison inmates, will be the direct\ beneficiaries of this inspiring message of the potential for change behind prison walls. As a captive audience, prisoners are removed from society, and denied access to many TV programs and books. The Producers plan to make The Dhamma Brothers available to prisoners and prison staffs throughout the United States.

“Takes you on a thrilling and hopeful voyage through a very dark place.” (Salon)

“Presents an intimate, compassionate and sympathetic portrait of a group of individuals that much of society has written off as savage and brutal and who reconnect to their humanity through the act of meditation.” (N.Y. Press)

This film, with the power to dismantle stereotypes about men behind prison bars also, in the words of Sister Helen Prejean (Dead Man Walking), “gives you hope for the human race."

- Omar Rahman - inmate at Donaldson Correctional Facility

“On the third day of meditation, I began to feel calm. And then and there, for the first time in my life, I was really ready to deal with me. A lot of guys was afraid to deal with Big Ed. And now I was ready to take him on, right there on that meditation mat.” - Edward Johnson - inmate at Donaldson Correctional Facility

The words of these men, prison inmates, capture the essence of The Dhamma Brothers. Their voices ring with the power and the truth of their experience. It is unlikely that the viewer, after seeing this film, will be able to return to old clichés and stereotypes about men behind prison bars. The Dhamma Brothers documents the extraordinary convergence of an overcrowded, understaffed maximum-security prison -- considered the end of the line in the Alabama correctional system -- and an ancient meditation program. East meets West in the Deep South.

Donaldson Correctional Facility is situated in the Alabama countryside southwest of Birmingham. 1,500 men, considered the state's most dangerous criminals, live behind high security towers and a double row of barbed and electrical wire fences. Yet within this dark environment, a spark was ignited. A growing network of men was gathering to meditate on a regular basis. Intrigued by this, Jenny Phillips, cultural anthropologist and psychotherapist, first visited Donaldson Correctional Facility in the fall of 1999. She planned to observe the meditation classes facilitated by inmates and to interview the inmate meditators about their lives as prisoners. As she met with the men, one by one in the privacy of an office, she was drawn in by their openness and willingness to talk freely about themselves. High levels of apprehension, distraction and danger characterize their lives as prisoners. Even though many of these men will never be released from prison, they were thirsty for meaningful social and emotional change. What she heard there was difficult to forget. It left her wondering if it were possible to live with a sense of inner peace and freedom within the harsh, violent prison environment.

As a meditator herself, Jenny knew that meditation directly addresses the issue of personal suffering, and offers a simple yet powerful means for obtaining relief from that suffering. But were these ancient ideas, as described in the teachings of the Buddha 2500 years ago, now relevant? Could the framework of this approach to suffering be translated into some basic principles of treatment that would be applicable to 21st century North American prisoners? Were these prisoners, many of them survivors of personal trauma, even capable of withstanding the emotionally and physically demanding experience of a 10-day meditation retreat? More important, was it possible for these men, some of whom had committed horrendous crimes, to change?

When returning home to Massachusetts, Jenny contacted the Vipassana Meditation Center in Shelburne Falls, Massachusetts, part of a worldwide network of centers dedicated to preserving meditation according to the teachings of Buddha. After a year of planning between the prison and the Vipassana staffs, in January 2002, Donaldson Correctional Facility became the first prison in North America to hold a 10-day Vipassana retreat.

The Dhamma Brothers tells a dramatic story of human potential and transformation as it closely follows and documents the stories of 36 prison inmates as they enter into this arduous and intensive program. It will challenge assumptions about the very nature of prisons as places of punishment rather than rehabilitation. Despite the extreme difficulty in obtaining permission to film inside a prison, the Alabama Department of Corrections allowed a film crew to document, not only the Vipassana retreat, but many other scenes and settings revealing the daily lives of prisoners and staff. The Dhamma Brothers draws the viewer in through memorable interviews with the inmates, the prison staff, the inmates' families, and members of the surrounding community.

The film combines verite footage and, because some of the inmates' crimes attracted significant media coverage, also includes archival television reports which appeared at the time of the crimes. In interviews immediately before the Vipassana retreat, the men openly express fear and trepidation, wondering what they will find when they look deeply within and face the consequences of past actions and trauma. They are shown packing their scant belongings and preparing for the journey inside, a very short walk down the prison corridor but a sea change in their lives as prisoners. We observe the transformation of the prison gym, a frequent site for violent battles among inmates, into a monastery, a separate, restricted place in which the inmate students can eat, sleep, and meditate in total seclusion from the rest of prison society. The Vipassana teachers, Bruce and Jonathan, prepare to live and meditate with the inmates. Teachers and inmates, men from culturally different worlds, are locked together in a dramatically revealing process. This is, most likely, the first time non-inmates have ever lived among inmates inside a prison.

We follow the men day to day on the retreat. Seated on meditation mats on a red rug donated by the Warden, wrapped in navy blue blankets, the men sit still in silence as they journey inside. Their days are punctuated by a strict daily routine of eating, sleeping and meditating.

Among those portrayed in the film are the following: OB: Sentenced to three life sentences for a drive-by shooting in which two were injured and one died. OB came to the U.S. from Africa as a teen-ager seeking freedom from civil war and violence in Uganda. When he was arrested in a high profile crime, he was

portrayed as a “ruthless animal from Africa”.

Grady: Serving life without parole, rescued from Death Row by a defense attorney the day before he was scheduled for execution. Grady discusses his crime as that of standing by while two men he had just met that day slaughtered a third man. He describes being frozen with fear while he witnessed the brutal attack, and then twenty years of guilt and remorse for being afraid to intervene.

Big Ed: Prison gang leader, held in a segregation cell for six years. Ed spent his years both in the streets and in prison ripping and running, with a reputation for being a tough guy.

In individual interviews after the Vipassana retreat, the men tell their tales of pain and self-discovery. During group interviews, the spiritual warriors of Donaldson Correctional Facility discuss their collective experiences and vow to try to maintain their nascent sense of solidarity. In the nameless, faceless anonymity of prison life, where daily life is organized around social control and punishment, Vipassana has offered an alternative social identity based on brotherhood and spiritual development. But, has the retreat been genuinely transformative for the men? Or, as the Warden suggests, could they just be faking these changes to look good to the parole board? Is the transformation sustaining?

In response to these questions we returned to the prison to interview the prisoners and prison staff to see the impact of the retreat upon their daily lives. We visited the homes of prisoners' families, and talked to them about their observations about the impact of the retreat. Also included are on-going personal letters and diaries from the inmates who have continued to corresponding with Jenny Phillips over the past four years.

The stories of the men at Donaldson Correctional Facility are those of the unseen, unheard, and underserved. This film shines a spotlight upon society's outcasts and untouchables. By witnessing these men on their odyssey into their misery to emerge with a sense of peace and purpose, there arises in the viewer identification with their quest. It is difficult to distance oneself from these men.

Suffering is universal. The men at Donaldson are learning to become free within even while their bodies are imprisoned. This film explores how free people are imprisoned inside, and will posit the possibility of freedom from that which imprisons us all. This is a compelling story showing the capacity for commitment, self-examination, renewal and hope within a dismal penal system and a wider culture bent on demonizing prisoners. We trust that the public airing of this documentary will engender a more informed understanding of the humanity within men and women serving time, and will encourage a call for the implementation of similar rehabilitation programs around the country.

This film will be of direct benefit to prisoners. Those most directly affected by the problems endemic in American prisons, the prison inmates, will be the direct\ beneficiaries of this inspiring message of the potential for change behind prison walls. As a captive audience, prisoners are removed from society, and denied access to many TV programs and books. The Producers plan to make The Dhamma Brothers available to prisoners and prison staffs throughout the United States.

“Takes you on a thrilling and hopeful voyage through a very dark place.” (Salon)

“Presents an intimate, compassionate and sympathetic portrait of a group of individuals that much of society has written off as savage and brutal and who reconnect to their humanity through the act of meditation.” (N.Y. Press)

This film, with the power to dismantle stereotypes about men behind prison bars also, in the words of Sister Helen Prejean (Dead Man Walking), “gives you hope for the human race."

The Dhamma Brothers Get Tickets

There are currently no showtimes for this film. Please check back soon.