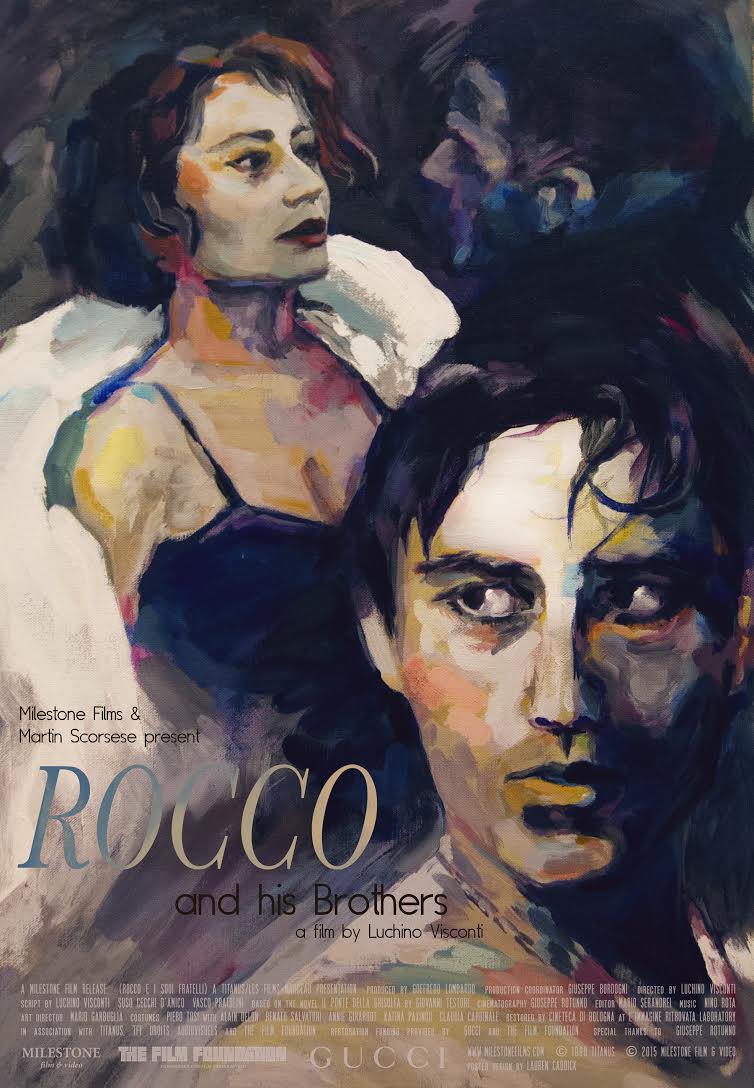

Rocco and His Brothers

Rocco is one of the most sumptuous black-and-white pictures I’ve ever seen.

-- Martin Scorsese

Rocco and His Brothers

“Fellini told the story of La Dolce Vita, the sweet life, but I instead will try to tell the story of the bitter life of people like Rocco.”

A new 4K restoration of Luchino Visconti’s Rocco and His Brothers (1960), starring Alain Delon, Annie Girardot, and Claudia Cardinale, will run at Laemmle Theatres beginning Friday, October 23. The new restoration is a Martin Scorsese and Milestone Films presentation.

Joining the tragic exodus of millions from Italy’s impoverished south, the formidable matriarch of the Parondi clan (Katina Paxinou, Best Supporting Oscar winner, For Whom the Bell Tolls) and her brood emerge from Milan’s looming Stazione Centrale in search of a better life in the industrial north. But, as they inch up the social ladder, family bonds are ruthlessly shredded, as the love of Delon’s saintly Rocco (“one of the most vivid and complex characters in all of Visconti’s work” – Vincent Canby) for prostitute Girardot drives brutish boxing sibling Renato Salvatori to rape and murder.

Simultaneously a documentation of a changing society; a kind of continuation of Visconti’s classic La Terra Trema; an evocation of the works of Sicilian titan Giovanni Verga, Dostoyevsky’s The Idiot, and Thomas Mann’s Joseph and His Brothers; and a visual tour de force as lensed by Giuseppe Rotunno (The Leopard, 8 1⁄2, Amarcord, All That Jazz, etc.), Rocco rocketed Delon and Girardot to international stardom and vaulted Visconti to his second triumvirate — here with Antonioni and Fellini — at the cutting edge of Italian filmmaking (his first, with Rossellini and De Sica, in the heyday of Neo-Realism).

The director’s personal favorite, Rocco’s mix of realism and intense, operatic emotion would profoundly influence the work of Coppola and Scorsese.

Rocco and His Brothers was restored by Cineteca di Bologna at L’Immagine Ritrovata laboratory in association with Titanus, TF1 Droits Audiovisuels and The Film Foundation. Restoration funding provided by Gucci and The Film Foundation. A Martin Scorsese presentation.

Rocco and His Brothers (Rocco e i suoi fratelli) is a film about emigration and marginalization. The film marked the first time Italian cinema took a look at relationships between deeply different cultures, a key element of the modern world. Today, Rocco and His Brothers is widely considered a classic and a masterpiece of Italian cinema. Yet while it was being filmed and after it was released in theatres, it was strongly opposed by the government of the time. Rocco and His Brothers became a kind of litmus test for Italian public opinion. At the start of the 1960s, Italy’s center-right government was experiencing a crisis, and at the same time the country’s Socialist party was growing and had seen great gains in the 1958 elections. Societal transformation and changes to traditional life were impacting Italian society and pushing it toward a political change that in 1962 would bring the first center-left government to power. During that critical phase of transition from a center-right government to a center-left government, ideological conflicts, violent reactions and heated debate between conservatives and progressives exploded, and cinema - the work of Luchino Visconti in particular - became a key battleground.

In this red-hot political climate and against a backdrop of seismic change, Visconti returned to the same discourse on society that he had undertaken in his earlier films, beginning, he said, with “The Earth Trembles (La terra trema) - my interpretation of I Malavoglia (The House by the Medlar-Tree). Rocco is basically the next episode in the series.”

Visconti began talks with Suso Cecchi d’Amico in the spring of 1958. The Milanese director described his idea to his screenwriter friend and to Vasco Pratolini as follows: “The story of a mother and her five sons: five like the five fingers on a hand, because it has to do with boxing.” Based on that beginning and on elements of the stories “Come fa, Sinatra?” and “Il Brianza” by Giovanni Testori, from the collection Il ponte della Ghisolfa (The Ghisolfa Bridge), a screenplay took shape. After Pratolini stepped away from the project to work on writing Lo scialo (The Waste), Enrico Medioli and later Pasquale Festa Campanile and Massimo Franciosa got involved. More than a year was taken up with preparing, planning, scouting locations, traveling to Basilicata and dealing with reams of documentation. Preparations went on for so long that Visconti had time to split from producer Franco Cristaldi, who wanted to force Brigitte Bardot on him. Thanks to Renato Salvatori, he met Goffredo Lombardo, a brilliant producer and the head of Titanus (who dreamed of casting Paul Newman as Simone).

Shooting began on February 22 (just a short time after La Dolce Vita premiered, right there in Milan, on February 5, 1960) and ended June 2, 1960. The Province of Milan would not allow Visconti to shoot the Nadia killing scene at the Idroscalo in Milan (an artificial lake), as it feared the place’s reputation would be tainted, so instead it was filmed on Lake Fogliano in the Province of Latina.

The film debuted at the Venice Film Festival, where it elicited strong reactions and great controversy. Pressure was put on the jury not to give it the Golden Lion, which instead went to André Cayatte’s Tomorrow Is My Turn (Le passage du Rhin).

The film premiered in Milan on October 14, 1960, and the following day the chief public prosecutor of the republic in Milan, Carmelo Spagnuolo, called in producer Goffredo Lombardo and demanded edits in four places that would cut a total of fifteen minutes out of the film. The film had already been rated, though, so Lombardo stubbornly resisted. He managed to obtain permission not to cut the scenes, but

instead to have them covered up during screening, with each individual projectionist responsible for deciding how to apply the prohibition. The system was so absurd that, of course, it couldn’t possibly work. Debate raged on for months, until February 1961, when Visconti’s new theatrical show, L’Arialda (Arialda) by Giovanni Testori, hit the stage in Milan and was banned due to obscenity by the same public prosecutor, who considered the work a kind of continuation of Rocco.

A new 4K restoration of Luchino Visconti’s Rocco and His Brothers (1960), starring Alain Delon, Annie Girardot, and Claudia Cardinale, will run at Laemmle Theatres beginning Friday, October 23. The new restoration is a Martin Scorsese and Milestone Films presentation.

Joining the tragic exodus of millions from Italy’s impoverished south, the formidable matriarch of the Parondi clan (Katina Paxinou, Best Supporting Oscar winner, For Whom the Bell Tolls) and her brood emerge from Milan’s looming Stazione Centrale in search of a better life in the industrial north. But, as they inch up the social ladder, family bonds are ruthlessly shredded, as the love of Delon’s saintly Rocco (“one of the most vivid and complex characters in all of Visconti’s work” – Vincent Canby) for prostitute Girardot drives brutish boxing sibling Renato Salvatori to rape and murder.

Simultaneously a documentation of a changing society; a kind of continuation of Visconti’s classic La Terra Trema; an evocation of the works of Sicilian titan Giovanni Verga, Dostoyevsky’s The Idiot, and Thomas Mann’s Joseph and His Brothers; and a visual tour de force as lensed by Giuseppe Rotunno (The Leopard, 8 1⁄2, Amarcord, All That Jazz, etc.), Rocco rocketed Delon and Girardot to international stardom and vaulted Visconti to his second triumvirate — here with Antonioni and Fellini — at the cutting edge of Italian filmmaking (his first, with Rossellini and De Sica, in the heyday of Neo-Realism).

The director’s personal favorite, Rocco’s mix of realism and intense, operatic emotion would profoundly influence the work of Coppola and Scorsese.

Rocco and His Brothers was restored by Cineteca di Bologna at L’Immagine Ritrovata laboratory in association with Titanus, TF1 Droits Audiovisuels and The Film Foundation. Restoration funding provided by Gucci and The Film Foundation. A Martin Scorsese presentation.

Rocco and His Brothers (Rocco e i suoi fratelli) is a film about emigration and marginalization. The film marked the first time Italian cinema took a look at relationships between deeply different cultures, a key element of the modern world. Today, Rocco and His Brothers is widely considered a classic and a masterpiece of Italian cinema. Yet while it was being filmed and after it was released in theatres, it was strongly opposed by the government of the time. Rocco and His Brothers became a kind of litmus test for Italian public opinion. At the start of the 1960s, Italy’s center-right government was experiencing a crisis, and at the same time the country’s Socialist party was growing and had seen great gains in the 1958 elections. Societal transformation and changes to traditional life were impacting Italian society and pushing it toward a political change that in 1962 would bring the first center-left government to power. During that critical phase of transition from a center-right government to a center-left government, ideological conflicts, violent reactions and heated debate between conservatives and progressives exploded, and cinema - the work of Luchino Visconti in particular - became a key battleground.

In this red-hot political climate and against a backdrop of seismic change, Visconti returned to the same discourse on society that he had undertaken in his earlier films, beginning, he said, with “The Earth Trembles (La terra trema) - my interpretation of I Malavoglia (The House by the Medlar-Tree). Rocco is basically the next episode in the series.”

Visconti began talks with Suso Cecchi d’Amico in the spring of 1958. The Milanese director described his idea to his screenwriter friend and to Vasco Pratolini as follows: “The story of a mother and her five sons: five like the five fingers on a hand, because it has to do with boxing.” Based on that beginning and on elements of the stories “Come fa, Sinatra?” and “Il Brianza” by Giovanni Testori, from the collection Il ponte della Ghisolfa (The Ghisolfa Bridge), a screenplay took shape. After Pratolini stepped away from the project to work on writing Lo scialo (The Waste), Enrico Medioli and later Pasquale Festa Campanile and Massimo Franciosa got involved. More than a year was taken up with preparing, planning, scouting locations, traveling to Basilicata and dealing with reams of documentation. Preparations went on for so long that Visconti had time to split from producer Franco Cristaldi, who wanted to force Brigitte Bardot on him. Thanks to Renato Salvatori, he met Goffredo Lombardo, a brilliant producer and the head of Titanus (who dreamed of casting Paul Newman as Simone).

Shooting began on February 22 (just a short time after La Dolce Vita premiered, right there in Milan, on February 5, 1960) and ended June 2, 1960. The Province of Milan would not allow Visconti to shoot the Nadia killing scene at the Idroscalo in Milan (an artificial lake), as it feared the place’s reputation would be tainted, so instead it was filmed on Lake Fogliano in the Province of Latina.

The film debuted at the Venice Film Festival, where it elicited strong reactions and great controversy. Pressure was put on the jury not to give it the Golden Lion, which instead went to André Cayatte’s Tomorrow Is My Turn (Le passage du Rhin).

The film premiered in Milan on October 14, 1960, and the following day the chief public prosecutor of the republic in Milan, Carmelo Spagnuolo, called in producer Goffredo Lombardo and demanded edits in four places that would cut a total of fifteen minutes out of the film. The film had already been rated, though, so Lombardo stubbornly resisted. He managed to obtain permission not to cut the scenes, but

instead to have them covered up during screening, with each individual projectionist responsible for deciding how to apply the prohibition. The system was so absurd that, of course, it couldn’t possibly work. Debate raged on for months, until February 1961, when Visconti’s new theatrical show, L’Arialda (Arialda) by Giovanni Testori, hit the stage in Milan and was banned due to obscenity by the same public prosecutor, who considered the work a kind of continuation of Rocco.

Genre

Drama,

Crime

Runtime

177

Language

Italian

Director

Luchino Visconti

Cast

Alain Delon,

Renato Salvatori,

Annie Girardot,

Katina Paxnou,

Roger Hanin

FEATURED REVIEW

Alan Scherstuhl, Village Voice

Life is uncertain and ever-shifting in Luchino Visconti's 1960 masterpiece Rocco and His Brothers, the tale of a family's migration from farmlife in southern Italy to Milan — and its near dissolution when faced with the city's temptations. This 4K digital restoration is gorgeous, of course ...

Played at

Royal 10.23.15 - 11.05.15

Playhouse 7 10.23.15 - 10.29.15

Town Center 5 10.23.15 - 10.29.15

Rocco and His Brothers Get Tickets

There are currently no showtimes for this film. Please check back soon.